All big corporations, especially service companies that have ongoing relationships with customers, e.g. power, telco, banks, are likely to have one thing in common … the existence of a contact centre (or call centre). Contact centres have been around for more than 50 years, with Pan Am (Pan American World Airways) being one of the first 24/7 contact centres; it provided customers a local phone number to ring for every market. With the advent of cheap telecommunication cost, contact centres are even based overseas in places where the staff cost is astronomically lower than the local environment.

Such corporations have quite similar goals for their contact centres and these can best be described below as follows:

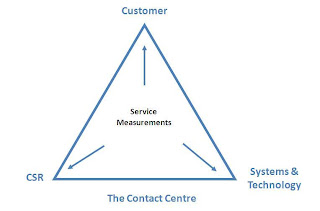

To bring about these goals, I have developed the Contact Centre Service Triangle to better explain the requirements of a contact centre.

- They want a customer’s query to be diagnosed accurately,

- They want a customer’s query to be resolved quickly, and

- They want a customer to finish the call with a positive impression of the Company.

The Customer

At the apex is ‘The Customer’. S/He is the most important reason for the existence of the contact centre. Hence, it is at the apex. At the base is the contact centre. It consists of TWO elements – CSR (Customer Service Representative – The human voice and front-facing staff with the customer) and Systems and Technology (The non-human elements that assist and track the performance of the contact centre).Right in the middle is ‘Service Measurements’ which are ‘measurements’ that we use to gauge how the contact centre is responding to the Customer.

For the ‘Customer’, there are THREE critical questions that we need to answer as follows:

- Why do customers ring a company?

- When do they call?, and

- How prepared are they to wait?

Why do customers ring a company?

Customers generally avoid calling a Company unless they have an issue. The best way to guide us to answer these questions is to work out the Product Life Cycle of the Company’s products involved. For example, customers may ring us because of one of these events:

- Enquire – A Customer rings to make an enquiry,

- Buy – A Customer rings to BUY something,

- Change – A Customer rings to change some details in their accounts,

- Pay & Bill – A Customer rings to pay or enquire about their bills,

- Resolve – A Customer rings us to fix something for them, and

- End – A Customer rings to terminate an account.

Knowing the relevant product life cycle will help the Company to structure its systems but more on that later.

When do Customers call?

Practically, any time but there will be certain patterns even within that ‘randomness’. However, there are THREE factors that we can cover off:

- It is possible to predict when customers generally call. There will be some predictable patterns, e.g. time of the day, and day of the week,

- Although we can ‘predict’ when calls come in (e.g. a Marketing campaign), they can still come into the centre in an erratic manner, and

- Finally, it is not possible to predict all call scenarios as human behaviour and the unfolding of daily events will impact on call arrivals.

A good contact centre is always using systems to capture the data so that it can analyse the predictable patterns and plan its staffing accordingly.

Next, how prepared are customers to wait?

Contact centres are built across the concept that ‘customers are prepared to wait on the phone’. This is what is termed as ‘Caller Tolerance’. There are possibly SEVEN factors that will impact on the way we plan staff resourcing and these are as follows:

- Degree of Motivation – If a Customer is experiencing severe inconvenience, e.g. power outage, they will most likely wait longer to reach their utility company than those with questions relating to their bills. If it is a case of medical emergency, you can assume that they will want an answer immediately.

- Availability of Substitutes – If the Customer is severely inconvenienced AND the telephone is THE ONLY mean of solving the problem, then they will stay on the line or keep calling

- Competition’s Service Level – The Competitor(s) will have an impact on the way that Customers view our resources,

- 0800 Line – Who is paying? For a 0800 line, customers may be encouraged to keep hanging on,

- Human Behaviour – The weather, a caller’s mood, the time of the day. Would you believe that there are more calls coming in when the moon is full?

- Level of Expectations – Customers in big metropolitan cities used to speed and convenience maybe less tolerable to wait, and finally

- Time Availability – Retirees would react quite differently from, say, stockbrokers.

Service Measurements

Remember, at the start, we said that the Customer is the most important reason for the presence of the contact centre. Having said that, ‘Service Measurements’ becomes the most important ‘next’ element. ‘Service Measurements’ are measurements designed to gauge the level of ‘quality services’ delivered by our staff to all customers. They represent the glue between the Customer and the Contact Centre.

‘Targeted scores’ are set, based on the Company’s understanding of customer and their needs as seen above. Any abnormalities will then be reported as they could represent issues. There are TWO types of targets:

- Service Level – It represents the level of tolerance set for calls; it is quantitative. In a one-sentence definition, it may be seen as follows - ‘Service Level’ is defined as the ‘X% of calls to be answered within Y seconds’. Here, we articulate that it is not just about answering the calls but answering them within an acceptable range as pre-defined by Management. Service Level should be tracked on a ½-hourly basis. (More on ‘Service Level’ in another write-up.)

Service Standards – These are the subjective ‘softer’ elements of service. They are behavioural – e.g. how are the CSRs performing in terms of ‘Call Opening’, ‘Establishment of Customer Needs’, ‘Hold/ Wait Protocol, and ‘Enthusiasm and Professionalism through the voice’?

Now, look out for Part 2 to conclude this write-up.

Now, look out for Part 2 to conclude this write-up.